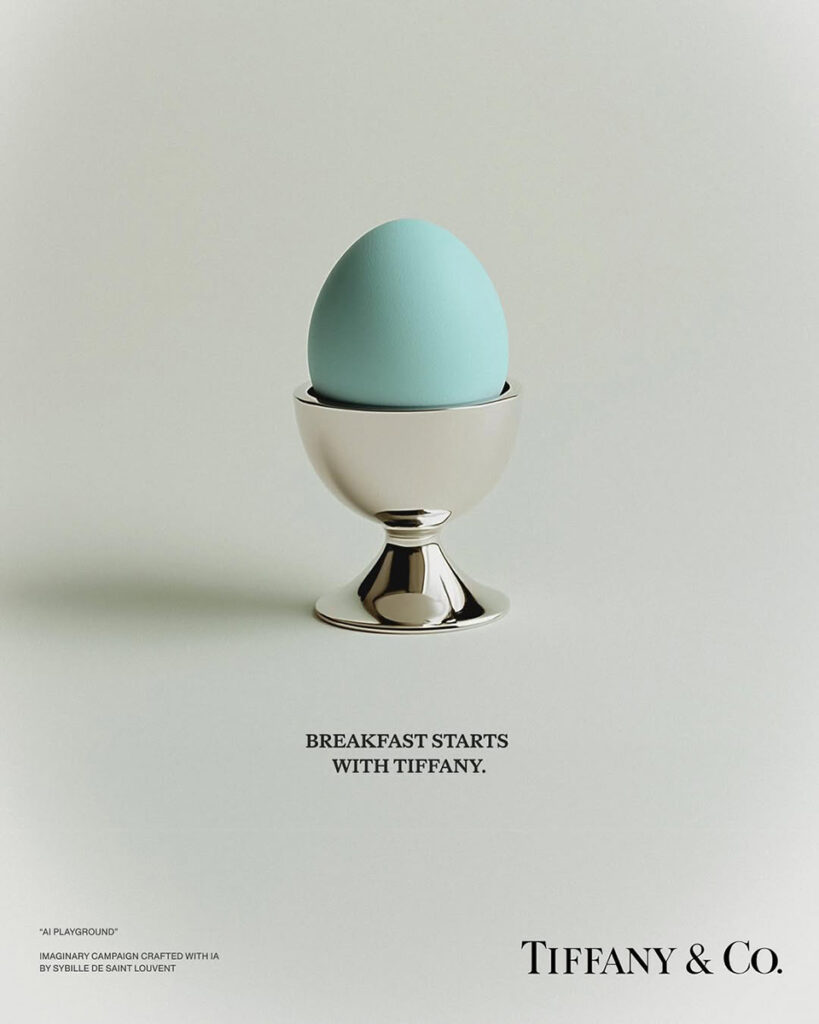

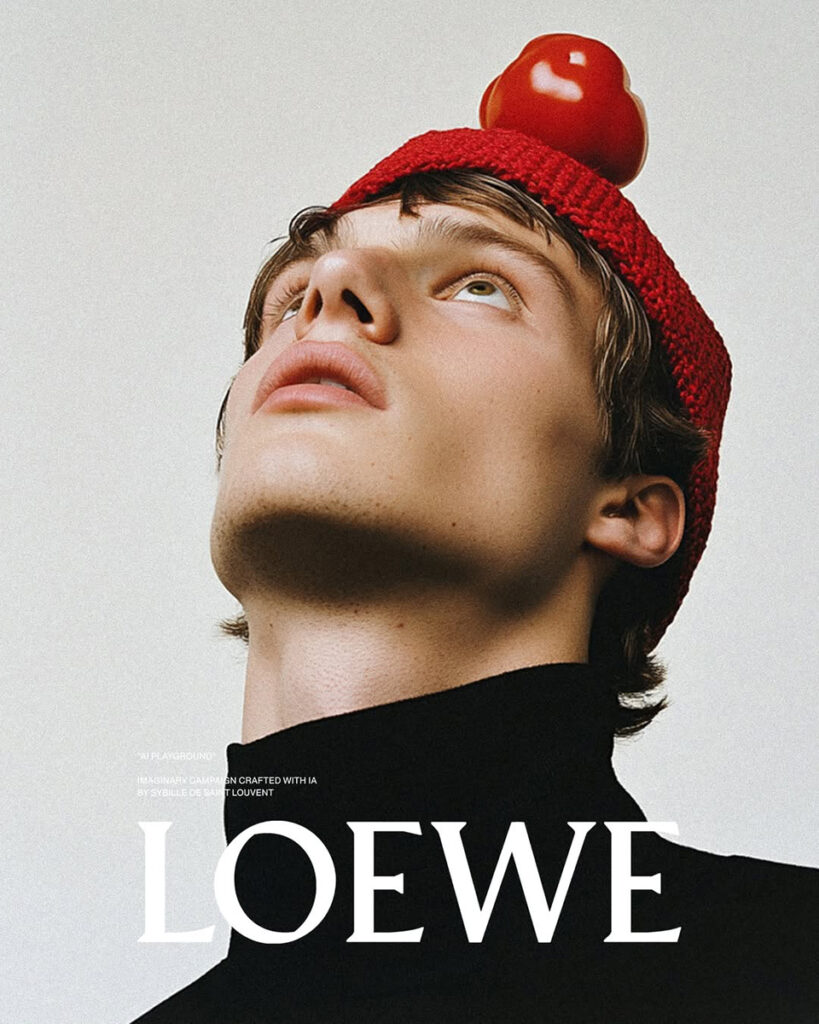

Sybille de Saint Louvent

Interview by Peter Cardona

1. You left formal studies to learn through observation and instinct. How has this shaped your vision

as an art director?

SSL. I didn’t leave formal studies by choice. It was more that I couldn’t find myself in what was

being offered. The French academic system is quite narrow, it pushes you to decide very early what

you want to do in life, at a moment when you’re still building yourself. There’s also a kind of

mathematical elitism that can quietly erode your confidence if you don’t fit into that mould. I think I

got caught in that trap.

Stepping out was almost a necessity, and it shaped my vision in a lasting way. When you’re not

taught within a predefined framework, you have to invent your own. You learn by observation, by

trial and error. That forces you to be creative, to find your own solutions instead of relying on

readymade ones. It also teaches you to stay endlessly curious. For me, that’s the fundamental spirit

of creation: to keep your eyes wide open, and to leave a little room for dreaming. It’s harder at

times, there’s no set structure to lean on, but it also frees you from certain codes. You stop looking

for validation, and start trusting what feels right for you.

2. Your website speaks of a “déjà-not-yet-vu.” How do you turn elusive sensations into concrete

visuals?

SSL. For me, creation starts with a tension, between something familiar and something slightly off.

That space of friction is where I find visual interest. I don’t try to control everything from the

beginning. I let language guide the image. Often, I write down fragments first, gestures, words,

small contradictions. Then I start to build around that. I think what we call “déjà-not-yet-vu” is

often a matter of rhythm, of silence, of detail. It’s a shift, something unsettling but elegant.

3. You’ve said that working with AI has made you more concise. How do you balance poetic

inspiration with linguistic accuracy?

SSL. I’ve often had very clear ideas in my mind, but the difficulty was in expressing them. Working

with AI has forced me to be more precise. The tool doesn’t guess, it executes.

So if I want it to reflect the idea I have in mind, I need to know exactly what I want to say, and how

to say it. It’s made me sharpen my language, not in a technical way, but in terms of clarity. It’s still

about poetry and emotion, but now I’m more conscious of how to translate that into a visual

direction. In a way, it’s helped me get closer to the core of what I want to tell.

4. Can you share a specific project or prompt where AI revealed something you wouldn’t have

imagined on your own?

SSL. There hasn’t been a project where AI revealed something already had in mind. Again, if we’re

strictly talking about artificial intelligence, it’s a tool for connecting ideas, not for inventing them.

The ideas always come from a human brain and AI doesn’t have opinions, it doesn’t take initiative,

and it doesn’t make decisions. It just executes 🙂 There’s no magic tricks. It can speed things up, or

offer variations, but it doesn’t create something that wasn’t already there in some form.

5. How do you integrate graphics, photography, and text in your concepts? Which medium

challenges you the most?

SSL. I tend to think in sequences, not necessarily linear, but narrative. So the idea is often the entry

point. Then comes the image, then the tension between the two. I love working with photography,

especially when it resists perfection. Graphics are less instinctive to me, they’re more mathematical,

more constructed. But I think the challenge isn’t the medium, it’s the space between them. That’s

where I try to create atmosphere in the transitions, not the elements.

6. You’ve mentioned drawing inspiration from emotions, memories, or sounds. Can you give an example of a project born from a non-visual stimulus?

SSL. It’s a bit paradoxical, because for me a sound, an emotion, a smell, or a memory will always

bring me back to an image, the two are intrinsically linked.

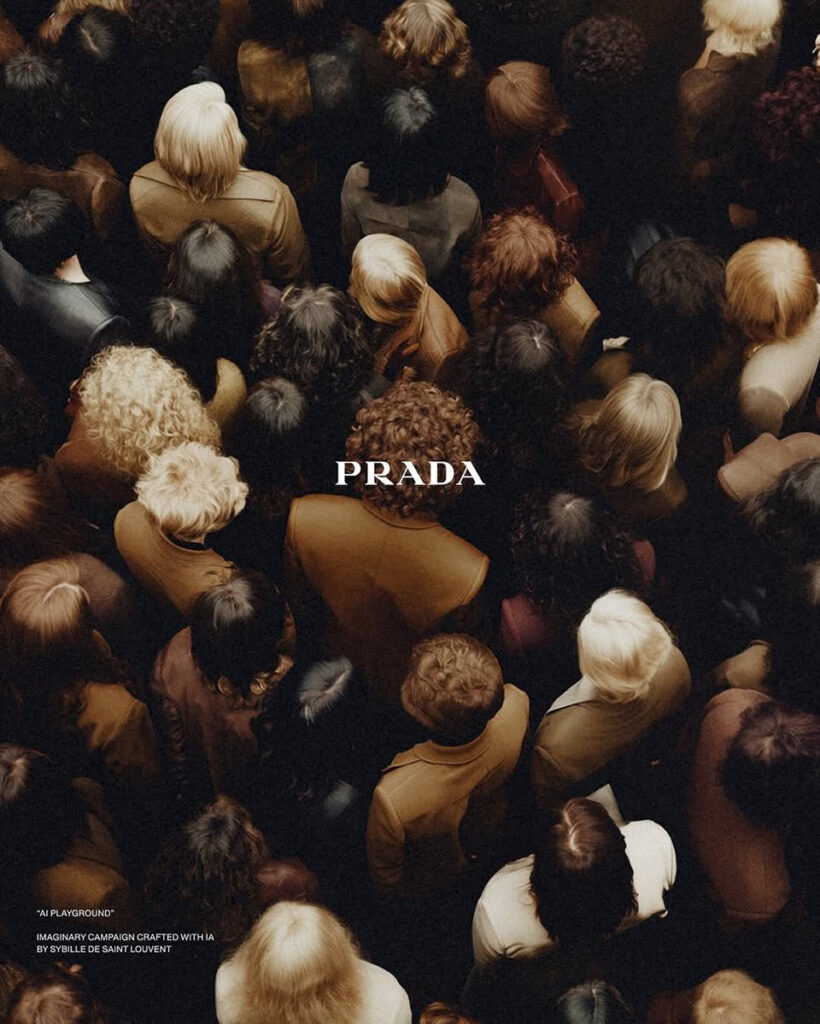

For example, I once created a fictional Prada campaign starting from nothing more than a song: I

Feel Love by Donna Summer. The track builds in rhythm and intensity, and as I listened, I

immediately saw a scene in my head, a chic, almost elegant rave, with a crowd seen from above.

Their jackets were arranged in a perfect color harmony, blending with the overall composition.

In my French mind, I feel love translated into a vision of people aligned, looking in the same

direction, united but still individual. I thought that was a beautiful message to carry visually.

7. You’ve said you prefer images that open up interpretive space rather than explain it. How do you

maintain that in commercial work for brands?

SSL. Honestly, I don’t really change my approach depending on whether the project is commercial

or not. The essence of my work is to tell a story. I’m not focused on presenting the product in a

perfect way — that’s not my role. If I were thinking in purely commercial terms, the product would

be huge, the logo everywhere, maybe even a price tag. But that’s not what interests me.

If you want to create real attachment to a brand, the worst strategy is to be purely commercial.

It might work in the short term, but it doesn’t build anything lasting. I believe you can write images

intelligently — leave space for the viewer to interpret, to project themselves, to play with the

language of the image.

I like to leave a certain zone of mystery, so the person engages with it and starts their own search.

It becomes a kind of visual conversation. In the end, the financial or commercial aspect isn’t really

my subject. My job is simply to tell stories.

8. You’ve noted how AI tends to reproduce Western aesthetics. What strategies do you use to

encourage cultural nuance and plurality?

SSL. This is a very current question. I don’t think I’m different from anyone else, I carry the same

biases as everyone. I was shaped by a very Western aesthetic, and it doesn’t come naturally to break

away from it. So I have to make a conscious effort: seek out visual and cultural references through

travel, immerse myself in the richness of the world we live in, and let that influence my work. It’s a

subject that genuinely concerns me. I don’t think we’re there yet, even though I can see that the

tools themselves have started integrating this idea into their parameters. A prompt I might have used

a year ago doesn’t get the same result today, there seems to be more built-in plurality in the way

they interpret.

Still, I think it’s essential to push for singularity. And that’s paradoxical, it’s obvious we should, but

it’s also difficult, because as social animals, we tend to look at each other and want to belong to a

group.

That instinct works against true plurality. There’s still a lot of work to do, and it’s not an easy topic.

9. What’s one misconception about AI art you wish to dispel—and what new responsibilities do you

see emerging?

SSL. There are so many. But I think the main one is this: AI is not a form of self. It’s not a mind.

It’s a tool, nothing more. Right now it’s everywhere in articles and conversations because it’s

recently become accessible to the general public. But AI has existed for years. What’s new is that

now anyone can use it, and that accessibility has made some people nervous.

We need to dismantle the idea that AI thinks for itself. The human is still the conductor. The

responsibility, though, is very real, especially in how and why we produce. There’s a growing habit

of creating images just to exist, whether as a brand or as an individual. But a lot of what’s being

produced isn’t necessary — not visually, not for knowledge, not for the human experience. That’s

what worries me: this bias towards speed and constant output.

The truth is, even if the tool is fast, the creative process still needs time. Whether you’re working on

a traditional shoot or with AI, good work requires reflection and concept time. The more time you

spend thinking, the better the result.

That’s something we can’t lose sight of. And despite appearances, AI is not endlessly flexible. I

often compare it to a capricious creative: you have to know how to guide it, be agile, but also accept

its limits. There’s still a lot of education to be done around how it works, and what it can and cannot

do.

10. What upcoming developments in AI—technological or cultural—excite or concern you the most

as an art director?

SSL. There are many also. I find it exciting to see collaborative AI platforms emerging, but what

really interests me is the short-term horizon, the next six months, the next year. I think that once the

current wave of visual AI hype settles, we might reach a point where the tool is better understood

and better handled.

For me, the future lies in using AI as a genuine creative tool, and integrating it into a process that

still involves stylists, make-up artists, set designers, all the essential talents that bring an idea to life.

The tool should support that ecosystem, not replace it.

I think we need patience. Once this phase of instinctive, sometimes unnecessary, overproduction

fades, AI could become a way to express ideas more deeply and push creativity further. That’s the horizon I’m looking towards, not speed for the sake of speed, but a richer, more thoughtful way of

creating.

11. What was the feedback from brands or the fashion world when you published your creations?

SSL. The response was very positive, because it felt like a new way of expressing ideas. The lack of

a clear legal framework does make some people uneasy, but the excitement was definitely stronger

than the fear.

I think part of the interest comes from the fact that we’ve been too product-driven for too long,

especially with the rise of new visual platforms. Now might be the time to focus on building

attachment to a brand, creating identity, working on each brand’s singularity rather than just the

object they sell.

So yes, the feedback was curious, engaging, and open-minded. I also had the chance to meet some

extraordinary people thanks to it.

12. Ask your readers a question

SSL. If beauty is a lens, when was the last time you swapped yours for another?

©RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA