A GENDERED AFFAIR

FASHION & INTERIORS: A GENDERED AFFAIR THE HOUSE AS BODY, THE BODY AS HOUSE — 150 YEARS OF WOMEN BETWEEN ORNAMENT AND AGENCY

A critical excavation where curtains become cages and shawls become revolution, from MoMu Antwerp

Grab a coffee or tea, sit down somewhere comfortable, and take a trip back in time with me.

There is a scene that has been repeated throughout more than 150 years of visual history: a woman sitting in her living room, dressed to match the curtains, the colors, the patterns, the sheen of the fabric. This is no coincidence, much less an accident of domestic coordination. It is a deliberate project, designed and executed with the purpose of similarity in mind.

The new MoMu catalog in Antwerp, reminds us that this chromatic harmony was never just aesthetic, but political, codified by gender, and always about who has the right to create and who is designed as a decorative object.

MATERIAL CONTRADICTIONS

The quote that opens the book is a punch in the stomach: “Her sphere is within the home, which she must ‘beautify,’ and of which she must be the ‘chief ornament,’” wrote Thorstein Veblen in 1899.

Reread it. Main ornament. Suddenly, all those paintings by Alfred Stevens take on new meaning, not just as portraits of contemplative bourgeois elegance, but as forensic documents of a perverse equation where woman equals decoration equals property. The painted portrait isn’t just the woman; it’s the woman as furniture, integrated into the system of objects that comprise the bourgeois interior.

Wim Mertens opens the historical narrative with the veritable drape mania that swept Europe between 1865 and 1890. Dresses became complex textile architectures, draped tabliers, protruding bustles, multiple layers supported by internal metal structures that weighed pounds. And the houses? Curtains upon curtains upon curtains, shawls artfully thrown over pianos as if they had just fallen there, yet carefully arranged, heavy portières separating each room, each passageway, fabric everywhere, concealing, protecting, suffocating.

Here is the twist that Mertens executes with precision: this excess functioned as fetish, yes, in the original sense of the word, an object invested with almost magical power. It also served as a defense.

The more ornate the woman and her home, the more layers of fabric between her and the world, the further she was from the harsh reality of industrial labor, male sweat, and the economic violence that sustained that luxury. The draperies were simultaneously a prison and a protection, a cage and a cocoon.

The bourgeois woman inhabited a material contradiction.

Within these constraints, however, women found space for agency. Dries Debackere’s meticulous research on cashmere shawls reveals how transformation became a form of resistance. These luxury items, which Robert de Montesquiou described with his usual flourish as “cloisonné enamels of wool, butterfly wings from Hindustan,” were symbols of unquestionable status. When fashion changed in the 1870s and the new bustle silhouette made it impossible to drape a shawl elegantly over the shoulders, women didn’t simply discard these expensive investments.

They transformed them. Cut the shawls into pieces, recombined motifs, created indoor dresses (tea gowns, robes de chambre), furniture covers, curtains, cushions, and table runners. A single shawl could be dismantled and reborn as five different objects scattered around the house. This wasn’t just frugal housekeeping. It was creativity exercised under brutal constraints. It was aesthetic decision-making combined with technical knowledge, cutting and recombining complex cashmere patterns required real skill, invisible labor that kept the bourgeois taste machine running.

The shawl circulated between body and space, between public and private, between fashion and decoration, challenging boundaries that were supposed to be absolute. If bourgeois ideology insisted on separating spheres (male/female, work/home, production/consumption), women’s material practice constantly merged them.

TOTAL CONTROL, FRACTURED REALITIES

The section on the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, is where the book really gains critical density. Lara Steinhäußer takes us through the Viennese ideal, as Josef Hoffmann designed literally everything in the Palais Stoclet for the Belgian couple. Architecture, garden, carpets, furniture, chandeliers, plates, cutlery, Madame Stoclet’s dresses, Monsieur Stoclet’s canes and ties. Total aesthetic control.

Paul Poiret visited and was visibly disturbed. “This substitution of the architect’s taste for the personality of the owners has always seemed to me a kind of slavery,” he wrote. The irony couldn’t be thicker, coming from a man who kept his own wife, Denise, as a living mannequin for his lifestyle brand, constantly photographed in carefully curated Atelier Martine environments. Poiret recognized the trap when applied to others.

Steinhäußer is careful not to reduce everything to simple oppression. Maria Sèthe at Villa Bloemenwerf embroidered complex textiles for the house, contributed to spatial decisions, and had a voice. Emilie Flöge had her own successful fashion house (Schwestern Flöge), collaborated with the Wiener Werkstätte as an equal, and was photographed by Klimt in dresses she co-created. The Gesamtkunstwerk had fissures. In those cracks, between ideal control and messy reality, women exercised real creative power, even if often uncredited in canonical design history.

Jess Berry traces how this concept transformed into what we now call “lifestyle branding.” Poiret understood that private life could be instrumentalized as a public spectacle. His barges, Amours, Délices, and Orgues, at the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, were total environments. Photographs circulated in Gazette du Bon Ton, Femina, Art & Décoration. He sold an entire aspirational existence, not just dresses.

Jeanne Lanvin offers a crucial contrast. As the first major female couturière to build a brand identity through interior design, she had something to prove.

Collaborating with Armand-Albert Rateau, she created salons, boutiques, and apartments unmistakably hers. The famous “Lanvin Blue” coordinated dresses and walls, creating a coherent brand experience.

The difference: when Denise Poiret posed at home, she performed Paul’s vision. When Jeanne Lanvin posed in her apartment with daughter Marguerite, she promoted her own. Autonomy versus instrumentalization. Creator versus creation. The Gesamtkunstwerk could be a cage or a territory, depending on who held the keys.

WHITE WALLS, RED CURTAINS

The discussion about modernism is where gender tensions explode. Adolf Loos wrote “Ornament and Crime” in 1908, equating excessive decoration with primitivism, childishness, and femininity. Le Corbusier followed the same script with almost religious fervor: immaculate white walls, pure forms, brutal functionality, total rejection of the “bourgeois” (always coded as feminine, always despised).

Ian Erickson reveals a delightful contradiction that cracks the entire facade of rational modernism. Le Corbusier, high priest of the machine for living, ordered himself a mysterious jaqueta forestière. French rural workwear, evoking pre-industrial craft tradition, is precisely the kind of nostalgia he supposedly rejected.

The male body could have its aesthetic idiosyncrasies; the female body had to be rationalized, standardized, and controlled. Robin Schuldenfrei does the essential critical work of resurrecting Lilly Reich from historical oblivion. Mies van der Rohe’s creative partner from 1927 to 1938, Reich played a pivotal role in the work that is now attributed exclusively to Mies.

The “materiality of modern design” we admire in the Barcelona Pavilion? It was Reich who selected and positioned all the velvet curtains, green, orange, black, and red, that divided and defined that space. Without these textile elements, the pavilion would be radically different, spatially incoherent.

While Mies is canonized as the “master of modernism,” Reich remained erased for decades, treated as a technical assistant, never as an intellectual author. This erasure is systematic, gendered, and structural. Textiles were coded as ‘feminine’ and therefore secondary to “serious” (masculine) architecture. Modernism was simply selective about which ornaments counted as legitimate and which contributions deserved authorship.

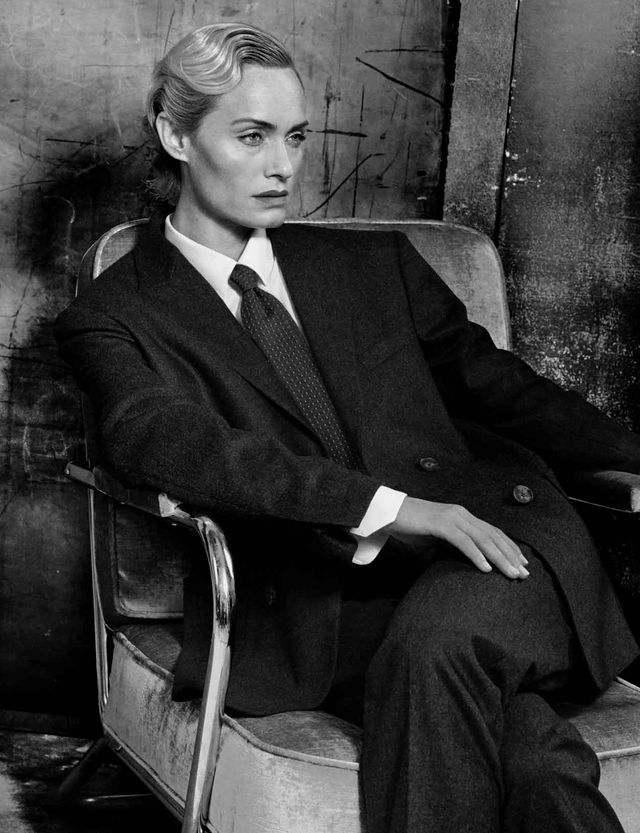

The book closes the circle by returning to Belgium, where it revisits the work of Ann Demeulemeester, Martin Margiela, and Raf Simons, the “Antwerp Generation” of the 1980s and 1990s. They transform the Gesamtkunstwerk, question it, and use it to explore identity, memory, and temporality in ways that would have been unthinkable to Hoffmann or Poiret.

Demeulemeester describes her home as an extension of the body, of the self. The peeling white walls, the found and aged furniture, the objects

accumulated over decades, everything resonates with her gothicomantic fashion language, her exploration of androgyny. Unlike Hoffmann’s total control, imperfection is embraced here, with marks of time and visible personal history.

Margiela is even more radical. His boutiques were anti-boutiques, bare white spaces in degraded locations, clothes presented on medical hangers or directly on the floor. His clothes featured deconstructed tailoring, exposed seams, and linings turned inside out. And his spaces deconstructed retail, removing all obvious branding.

Demeulemeester describes her home as an extension of the body, of the self. The peeling white walls, the found and aged furniture, the objects

accumulated over decades, everything resonates with her gothicromantic fashion language, her exploration of androgyny. Unlike Hoffmann’s total control, imperfection is embraced here, with marks of time and visible personal history.

Margiela is even more radical. His boutiques were anti-boutiques, bare white spaces in degraded locations, clothes presented on medical hangers or directly on the floor. His clothes featured deconstructed tailoring, exposed seams, and linings turned inside out. And his spaces deconstructed retail, removing all obvious branding.

The parallel: exposing the construction. Both the clothing and the commercial space. Simons works with architecture and memory, Bauhaus and rave culture, Kraftwerk and suburban youth. When he designs furniture or installations for fashion shows, he creates environments that are simultaneously cold (modernist geometry, industrial materials) and warm (laden with nostalgia, subcultural resonance). It’s a Gesamtkunstwerk permeated by melancholy, by the awareness that totality is always an illusion, always temporary.

150 years after Veblen, we are still negotiating the precise boundaries between the interior and exterior, the public and private, and the body and space. Now with a critical awareness of what is

at stake.

WHY NOW?

The book is also important because it asks ques tions that remain uncomfortable: Who has the right to the Gesamtkunstwerk? When does the total work of art become a trap? How can we separate genuine creativity from masked control,

such as curation? And the question that resonates loudest: how to tell this 150-year story without reproducing the same erasure we criticize, without forgetting the Maria Sèthes, the Lilly Reichs, the anonymous women who cut and recombined shawls, who were simultaneously muses, collaborators, creators, and prisoners of their own good taste?

In the end, what Romy Cockx and her team deliveris more than a beautiful museum exhibition catalog.

It is a careful archive of unresolved contradictions: women as ornaments and as agents, houses as prisons and as territories of hard-won power, clothes as uniforms of conformity and as statements of autonomy. It is history told through curtains, shawls, dresses, chairs, and architectural plans, and none of these objects are just what they seem at first glance.

The final lesson is perhaps this: pay attention to materiality, to concrete objects, to the everyday practices of making and inhabiting. Because it is in these seemingly decorative details that power relations become visible.

And it is also there that resistance can be exercised, even in brutally limited conditions. Sometimes, transforming a shawl into a curtain can be a revolutionary act.

Fashion & Interiors: A Gendered Affair is available through Hannibal Books. The catalogue documents the eponymous exhibition at MoMu Antwerp, curated by Romy Cockx.

Review by Brenda Barreiros